- Home

- Ray Suarez

Latino Americans Page 12

Latino Americans Read online

Page 12

The “drapes” of Harlem, featuring high-waisted pants with legs ballooned at the knees, narrowing to a tapered “pegged” ankle, held up by dressy suspenders, topped with a jacket that reached the knees with a cinched midsection and flamboyantly padded shoulders, were embraced by Southern Californians in the early war years.

In wartime, the production of automobiles built for civilian use was severely curtailed, gasoline and meat and much else was rationed, and the zoot suit was also banned, because it used so much fabric. The June 21, 1943, edition of Newsweek said that despite the War Production Board ruling, “the zoot suit has continued to thrive—mainly through the diligence of bootleg tailors.” Seven decades later it may seem a little silly to take youth fashion so seriously as a possible source of rebellion in wartime. Newsweek concluded that the U.S. government was taking no chances. “The War Frauds Division got an injunction forbidding one shop to sell any of the 800 zoot suits in stock. Claiming that the shopkeeper had contributed to ‘hoodlumism,’ agents said they had found that great numbers of zoot coats and pants were being made in New York and Chicago.”

What could be better for an eighteen-year-old eager to signal his membership in a distinct culture? Your parents, often Mexican-born, tried to attract as little attention to themselves as possible and wanted you to do the same. You adopted a new barrio language, Caló, mixing archaic Spanish, English, and the Spanish of Mexico. Caught out between two cultures, not quite at home in either, you could now invent yourself.

The invented self who emerged on the streets of Southwestern cities was the pachuco, a working-class kid with his own clothes, his own language, a gravity-defying, swooping marcel-style hairdo (short on the sides with long waves of hair atop the head held in place by gel), and a street posture meant to signal a cool contempt for the conformity to the mainstream that was desired by worried parents and white authority figures.

Drop into this volatile mix a state on edge from fear of foreigners, suspicion of infiltration of fifth columnists (residents in sympathy with a country’s external enemies), and wild rumors circulating about the Nazi recruitment of Mexicans in California. Something was bound to happen, and it did.

In Los Angeles on the night of June 3, 1943, a sailor thought a pachuco was lunging for him, and a fistfight started. Fights between zoot-suited young men and soldiers and sailors escalated into days and nights of street battles. The newspapers, the police, and elected officials quickly took sides, and it was no surprise that public opinion landed heavily on the side of uniformed servicemen.

Once the violence began, it grew, and spread. On June 7, the Los Angeles Times warned of storms ahead. Instead of heading off the trouble, the newspaper helped get the word out. Men in uniform began to drive in from as far away as Las Vegas to get in on the action. Some two thousand soldiers and sailors rushed into private homes and movie theaters looking for young zoot suiters to beat up. Eventually the crowd was stopping cars on the street, dragging away drivers and passengers, and destroying the cars.

For more than a week groups of men, soldiers, sailors, and their allies set upon Mexican teens, often stripping them down to their underwear right on the streets and setting their clothes on fire. Even as the violence subsided in the city of Los Angeles, it spread to the nearby cities of Pasadena and Long Beach, and as far away as San Diego and Phoenix. This wasn’t just about clothes and youthful rebellion anymore. Latinos may have been the first victims, but they were eventually joined by African-Americans, Asians, and their white friends. If you were different enough, you were fair game.

It’s a small thing, but notice: In much the way massacres of American Indians ended up being called “battles” in history books, the disturbances came to be known as the Zoot Suit Riots, not “the Sailor Riots” or “the Soldier Riots.” In this one small turn of a phrase, victim becomes perpetrator; the target becomes the cause.

Eventually, investigations, hearings, and inquiries would conclude that the sailors started the riots. While no sailors were arrested or charged with a crime, more than five hundred Latinos were charged with crimes such as assault, disorderly conduct, and vagrancy. The Los Angeles Times, after playing a role in raising the temperature on the streets of the city, went as far as to run a headline: “Zoot Suiters Learn Lesson in Fight with Servicemen.” Commission findings did not matter. The Times verdict more likely mirrored the attitudes of many of its Anglo readers: “Those gamin dandies, the zoot suiters, [have] learned a great moral lesson from service men, mostly sailors.” Gamin is not a word used in newspapers today. It means a raggedly dressed street child.

“All that is needed to end lawlessness is more of the same kind of actions that is [sic] being exercised by the servicemen,” the LA Times went on. “If this continues, zooters will soon be as scarce as hen’s teeth.”

After years of economic depression, the sailors roaming the streets looking for Mexican teenagers probably were not all that different in socioeconomic terms from their targets. In June 1943, all a poor kid from Anywhere, USA, had to do to separate himself from working-class Latinos in southern California was put on a uniform.

Zooters were, from the outset, heavily Latinos. Yet the media accounts of the riots, and the investigations that followed, played down the ethnic identity of the boys who were beaten, stripped, and hunted in their own hometown. The Los Angeles Times chose to stress cultural and social differences, rather than ethnic ones, telling its readers racial prejudices were not a cause or catalyst, because zoot suits were worn by many different races.

What had the Mexican and Mexican-American young men done? Their main offense was just being who they were. Not only were they “outsiders” (a peculiar designation for residents of a city founded by a column of Spaniards, Indians, and mestizos coming up from Mexico and naming their city for a revered title of the Virgin Mary, the Queen of Angels), but they were outsiders exuberantly embracing a separate style of dress, of speech, even their own dances. They were not hiding. They were not pretending to accept mainstream Anglo norms.

In his book on the zoot suiters, University of Southern California historian Mauricio Mazón grasps the strangeness of the fights on the streets. “They are a remarkable event in that they defy simple classification. They were not about zoot-suiters rioting, and they were not, in any conventional sense of the word, ‘riots.’

“No one was killed. No one sustained massive injuries. Property damage was slight. No major or minor judicial decisions stemmed from the riots. There was no pattern to arrests. Convictions were few and highly discretionary. There were no political manifestos or heroes originating from the riots, although later on the riots would assume political significance for a different generation. What the riots lack in hard incriminating evidence, they make up for in a plethora of emotions, fantasies, and symbols.”

Those ten nights in Los Angeles have launched dozens of books and articles, films and theatrical works. History, and memory, can accomplish odd and useful things. Mexican-American community organizations in Los Angeles had already been jolted into action by what came to be called “the Sleepy Lagoon Murder,” the killing of a Mexican-American man, José Díaz, in 1942. Though Díaz’s fatal wounds were consistent with being hit by a car, almost two dozen Latino men who had been fighting were charged with involvement in Díaz’s death.

Several were acquitted on all counts, but twelve of the young men were convicted of three serious charges: murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and intent to commit murder. An all-white jury sentenced three of the young men to life in prison, and three others were given five years to life. To the wider Anglo world, the murder was a sign of the delinquency and danger associated with Latino young men. To the Mexican civic leaders of Los Angeles, it was a reminder of the suspicion, contempt, and ignorance that shaped the majority view of their lives.

A group calling itself the Youth Committee for the Defense of Mexican American Youth wrote a letter to Harry Truman�

��s vice president, Henry Wallace, one of the most liberal politicians ever to hold high public office in the United States. The strategy behind the letter was straightforward, astute, and at the same time strangely touching. The committee told Vice President Wallace, “We feel you should know about the bad situation facing us Mexican boys and girls and our whole Spanish-speaking community.”

The note went on to tell of the accused in the Sleepy Lagoon Murder, conceding that some were no angels, but offering a glimpse of day-to-day life in el barrio. “These 24 boys come from our neighborhood. In our neighborhood there are no recreation centers and the nearest movie is about a mile away. We have no place to play so the Police are always arresting us. That’s why most of the boys on trial now have a record with the Police.”

Then the letter turned an important corner and got down to business. The young people, in effect, told Henry Wallace, This is what our lives are like, Mr. Vice President. Some of us work in defense plants. Many of us have older brothers fighting in the Pacific: “There is still a lot of discrimination in theaters and swimming pools and the Police are always arresting us and searching us by the hundreds when all we want to do is go into a dance or go swimming or just stand around and not bother anybody. They treat us like we are criminals just by being Mexicans or of Mexican descent.”

The letter continued with a plea for prowar educational materials in Spanish and English, more volunteer opportunities and access to public places, and relief from the discrimination the young people saw in their daily lives. Just to reiterate, one last time, the letter closed, “We don’t like Hitler or the Japanese either.”

The arrests immediately following the death of José Díaz set off a wave of anti-Mexican panic. Southern California newspapers called for a crackdown, and police departments responded with hundreds of arrests of young Mexican men on a wide variety of charges.

The Sleepy Lagoon convictions were overturned on appeal in 1944. In reviewing the record of the first trial, the appellate judge found a long list of irregularities: The crowded courtroom made it impossible for the accused to sit with their own lawyers; the sarcastic and dismissive trial judge, Charles W. Fricke, consistently treated all attempts by defense lawyers to protect their clients’ interests with withering contempt. The evidence presented at trial, the appeals court found, was contradictory, unsubstantiated, and insufficient to sustain guilty findings in charges as serious as murder.

Yet the judge would not concede that the Sleepy Lagoon defendants had received unfavorable treatment in court because they were “of Mexican descent.” He noted that the murder victim, José Díaz, was also Latino, as were the young men injured in a group fistfight leading up to the arrests. The reversal shot down accusations of prejudice as bluntly as it shot down the convictions by concluding, “. . . there is no ground revealed by the record upon which it can be said that this prosecution was conceived in, born, or nurtured by the seeds of racial prejudice.

“It was instituted to protect Mexican people in the enjoyment of rights and privileges which are inherent in every one, whatever may be their race or creed, and regardless of whether their status in life be that of the rich and influential or the more lowly and poor.”

• • •

THE ZOOT-SUIT RIOTS and their aftermath were understood very differently by Latinos. Looking back, José Ángel Gutiérrez noted the paradox of Americans fighting Americans during wartime. “This was happening as the US was fighting the Nazis. America was supposed to stand for tolerance, for equality. Yet servicemen were bashing [the] hell out of other Americans because they weren’t standard-issue white Americans—at a time when Mexican Americans were making a mighty contribution to the war effort. These beatings and the humiliation colored the worldview of generations of Latinos to come. People like me.”

People like me. It is a vitally important phrase to keep in mind as the Second World War moved toward its conclusion. What could Latinos have concluded in the 1940s about their fellow citizens? Did the others think we were equal? Did they think we were Americans? Did they even think we were “doing our part” to win this war? For Mexican-American civic leader Paul Coronel, speaking at a public meeting, the answer to all was clearly no. “American people have not regarded the Mexican American as an equal, racially or economically. Our American institutions, our schools, communities, [and] churches, have regarded the Mexican as a problem and not as an asset to our American society.”

Beating the Japanese and Germans was going to be one thing. Defeating entrenched social norms and long-held stereotypes was going to be more complicated. A new fight began for thousands of servicemen: The freedom and liberation American soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines had brought to people around the world now had to be secured back home.

Millions of people who helped the United States win the war were coming home hoping for their share of the victory, and a “return to normal.” At the same time the old normal was not going to be good enough for men who had advanced in uniform, risen in status, and might not be willing to simply return to the life they left behind years before. A returning veteran noted, “Mexican-American soldiers shed at least a quarter of the blood spilled at Bataan [a brutal battle to recapture the Philippines]. What they want now is a decent job, a decent home, and a chance to live peacefully in the community.” A Mexican-American newspaperman echoed that hope. “After this struggle, the status of the Mexican-Americans will be different.”

• • •

IN SEPTEMBER 1945, just a few weeks after he was celebrated by the new president, Harry Truman, who draped the country’s highest military honor around his neck, the “Fearless Mexican,” Macario Garcia, came home to Texas. He spoke before the Houston Rotary Club and was celebrated at a party and dance by the League of United Latin American Citizens, LULAC, near his hometown of Sugar Land.

It was the next day, September 10, 1945, that Garcia stopped at the Oasis Café for a soda. Newly demobilized servicemen and -women were everywhere in those days, in ports and railroad stations, streaming out of bases and forts onto the streets of cities and towns. Back home, Sergeant Garcia was not a decorated hero, not the “Fearless Mexican” of newsreels and press releases. For some, he was still just a Mexican.

He was refused service. A sign in the restaurant window read, NO DOGS, NO MEXICANS. Mac Garcia knocked over tables and broke windows. He punched the woman who owned the place in the mouth, and was attacked by her brother, holding a baseball bat. When the fight was over, the Medal of Honor recipient was arrested for aggravated assault. Extraordinary heroism on the battlefield wasn’t going to be enough. The Bronze Star ribbon on your uniform that told the world you were ready to bleed for your adopted country, and the Purple Heart that showed you had, weren’t going to be enough.

In the bad old days, Macario Garcia might simply have been thrown into jail, without too many questions about the circumstances of the fight, or who might have been at fault. In 1945, even in Texas, it made a big difference if a Mexican dragged out of a fight had just won the Medal of Honor.

National radio star Walter Winchell, nobody’s idea of a liberal but a man who knew a good story when he saw one, took to the airwaves. “This hero . . . [who] fought for our country and won the highest award our country can give, is named Sergeant Marcio [sic] Garcia, a Mexican. He was refused service, though he was wearing the United States uniform at the time. The persons responsible for this dreadful assault could hardly be Texans. Texans do not fight with baseball bats.”

Since Texas split from Mexico a century before, cases like this attracted little attention. A Mexican was charged with a crime. An Anglo prosecutor brought the case; a mostly Anglo or all-Anglo jury heard the case. Guilty as charged. Mac Garcia, however, was a Mexican with a Medal of Honor. Network and syndicated media had new reach and power, and could make national stories out of local ones. Garcia also had LULAC, the Hispanic civil rights organization founded in 1929 in his corner, and LULAC had fri

ends. Garcia was defended in court by John Herrera, a descendant of historic figures in Texas history who was to become a LULAC national president, and later was defended by former Texas state attorney general James Allred.

“Mac” Garcia’s travels in Texas were well-covered in the state press after he returned from Washington with the country’s highest military honor. When he was refused service in a South Texas café, the story was eventually covered nationwide. CREDIT: NARA

National and regional press flocked to the story. In the glare of national attention, the case was repeatedly postponed and then quietly dropped. Like so many of his wartime comrades, Garcia moved on to the business of living. He became an American citizen, got married, had three kids, finished his high school diploma. As if to illustrate the duality, the twin identities of Latinos, Garcia also earned the rare distinction of receiving one of Mexico’s highest military honors, the Mérito Militar.

When he died in a car crash in 1972, the Houston City Council named a street in his honor. The Macario Garcia Army Reserve Center was dedicated by Vice President George H. W. Bush, and a middle school now bears his name in his hometown of Sugar Land. Just half a century separated a decorated vet and his encounter with a No Dogs, No Mexicans sign, and a school dedicated to his memory.

Untold thousands of Latino vets went home, like other Americans, and got started in civilian life. Indignities large and small were visited on other returning Latino soldiers, sailors, and marines who had not been given the country’s highest award for bravery.

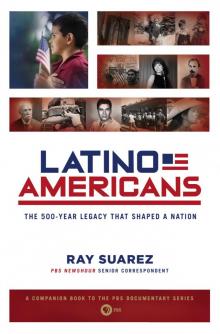

Latino Americans

Latino Americans